Gander’s Diversion Playbook: How a Remote Airport Turned Two Weather Diversions Into a Masterclass

When winter clamps down on Newfoundland, the flying public often sees only the end result: a “diverted” notification, a long night, and a rebooked itinerary. What happened this week in central Newfoundland shows the other side of the operation—how a small station can absorb a sudden spike in passengers and still keep the system moving.

On Wednesday night, two Air Canada flights bound for St. John’s International Airport (YYT) were unable to land due to deteriorating weather. Both aircraft diverted to Gander International Airport (YQX), an airport with long runways and diversion DNA—but a limited number of hotel rooms and taxis. Roughly 200 passengers and crew were suddenly on the ground in a town with four hotels and only a handful of cabs available.

Instead of spiraling into the familiar “sleep on the terminal floor” scenario, Gander executed an impromptu, community-backed IROPS response that got passengers into rooms quickly and back to the airport the next morning with minimal friction. For airline and airport professionals, the story isn’t just heartwarming—it’s operationally instructive.

Two flights, one destination, and a hard stop at YYT

The diverted flights were Air Canada Flight AC690 from Toronto Pearson International Airport (YYZ) to St. John’s (YYT) and Air Canada Flight AC674 from Montréal–Trudeau International Airport (YUL) to St. John’s (YYT). Both services were operated by Airbus A220-300s—an aircraft type that has become the backbone of many Canadian domestic schedules because it offers near-mainline comfort with narrowbody economics.

The A220-300 is particularly well-suited to routes like YYZ–YYT and YUL–YYT: it has the legs, the payload flexibility, and the passenger appeal. In Air Canada’s standard two-cabin layout, the A220-300 typically seats 137 passengers in a 2-2 Business Class and 2-3 Economy Class configuration, eliminating the “every row has a middle seat” pain point common on other single-aisle fleets. Powered by Pratt & Whitney PW1500G geared turbofans, the type is optimized for efficiency and range in a size category that airlines can profitably deploy across thinner markets and shoulder-season demand.

One of the diverted aircraft, C-GNBN, is also well known to enthusiasts and industry watchers: it wears Air Canada’s Trans-Canada Air Lines retro livery—a branding nod that stands out on any ramp, even in poor weather.

With YYT unavailable, the operational question becomes immediate: where do you send two A220s with full loads when the local weather is closing in and alternates are filling up?

Why Gander (YQX) is the “obvious” alternate—until it isn’t

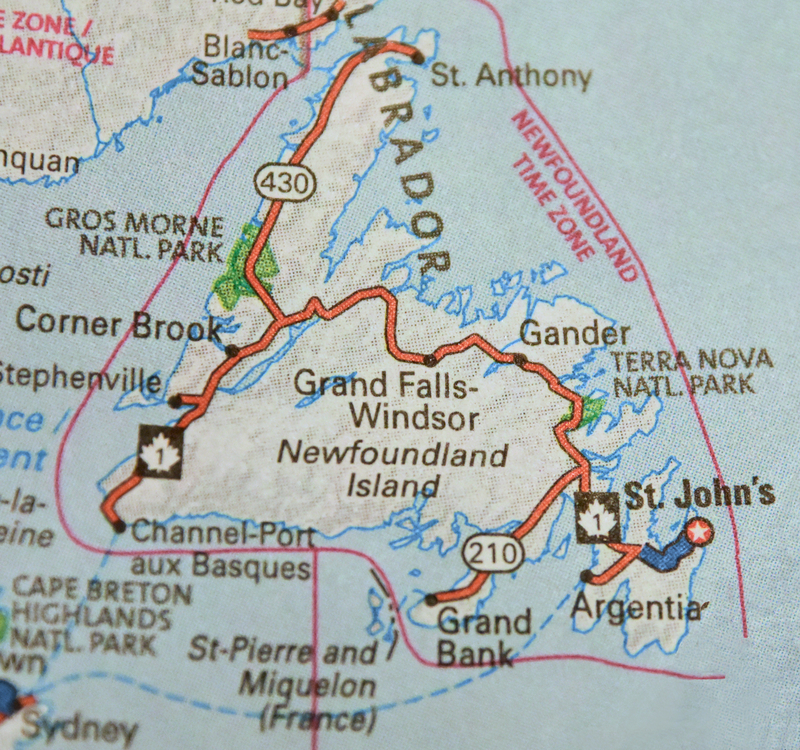

On a chart, Gander (YQX) makes a lot of sense as an alternate for St. John’s (YYT). It’s close enough to keep the flight legal and the duty day manageable, while still offering real infrastructure. YQX’s primary runway, 03/21, stretches 10,200 feet—long enough for everything from domestic narrowbodies to widebodies on transatlantic diversions. The airfield’s history is built around irregular operations: it was once a key transatlantic refueling stop, and the airport retains the physical plant that comes from that era.

But airports aren’t just asphalt and approach lighting. They’re beds, buses, staffing, and process.

When AC690 and AC674 arrived unexpectedly, Gander’s constraint wasn’t runway capacity. It was ground logistics: moving hundreds of people from a terminal to four hotels in winter conditions with limited commercial transport options.

That’s where the night’s defining moment happened—off-airport, off-radio, and completely outside any formal airline station manual.

The Facebook post that replaced a bus contract

A call came into the Quality Hotel and Suites in Gander shortly after the diversions: rooms were needed, immediately. The passengers could be spread across the town’s four hotels, but there were only a few taxis on the road. At 10:03 p.m. local time, hotel staff posted in a local Facebook group asking for help—more than 100 people were still waiting at Gander International Airport (YQX) for rides.

Within minutes, residents began driving to the terminal and shuttling passengers to hotels. The result was remarkable not because it was charitable—Newfoundland communities are known for that—but because it solved the exact problem that breaks diversion recovery: the gap between aircraft arrival and passenger accommodation.

From an operations perspective, this is the point where diversions either stabilize or metastasize. If passengers can’t get to hotels, the crew often can’t either. If the crew can’t rest, the aircraft can’t reposition. If the aircraft can’t reposition, the next day’s flying starts out of position and the disruption ripples across the network.

In other words: getting people into beds is not customer service. It’s fleet protection.

The next-day recovery: short hops, big implications

The following day, both aircraft continued on to St. John’s (YYT) from Gander (YQX) after the weather eased and recovery planning solidified.

Operationally, this is where the A220’s role becomes clear. These were not rescue widebodies with excess slack in the schedule; they were revenue aircraft in a tightly timed domestic bank. The faster the operator restores the hull to its planned sequence, the less secondary damage hits downstream rotations, crew pairings, and maintenance planning.

The post-diversion sectors were short—Gander (YQX) to St. John’s (YYT) is a quick leg by jet standards—but the value wasn’t in miles flown. It was in putting aircraft, crews, and passengers back into the flow of the network.

The part everyone remembers: Gander has done this before

Any mention of Gander (YQX) inevitably carries the shadow—and pride—of September 2001. During Operation Yellow Ribbon, 38 aircraft diverted into Gander, bringing more than 6,000 passengers plus hundreds of crew into a town that simply wasn’t built for an overnight population surge. The story later inspired Come From Away, which turned an aviation contingency plan into cultural history.

Even airline branding has nodded to it: Lufthansa once named an Airbus A340-300 “Gander/Halifax,” a rare non-German city pairing in an otherwise German-city naming tradition.

This week’s diversion was smaller in scale, but the operational theme was identical: the airport and community acted as a pressure valve for the network when the primary destination couldn’t accept arrivals.

Bottom Line

Gander International Airport (YQX) didn’t “fix the weather” at St. John’s (YYT). What it did—quickly and effectively—was protect the system around the weather.

Two Air Canada Airbus A220-300 flights (AC690 from Toronto/YYZ and AC674 from Montréal/YUL) diverted into a small station with limited hotels and limited taxis. Within an hour, local volunteers had passengers moving, crew rest became achievable, and the next-day recovery to St. John’s (YYT) was possible without turning a pair of diversions into a multi-day network headache.

For airline professionals, the lesson is straightforward: diversion planning isn’t just alternates and fuel. It’s ground truth—beds, transport, communications, and the ability to improvise when contracts and capacity run out. Gander (YQX) has a reputation for that. This week, it earned it again.